Inclusive curatorial practice requires the input and voices of stakeholders. It must be accessible to all visitors, honor the cultural context of objects (even when that means not putting objects on display or repatriating them), and respond to the moral mandate for equity by using exhibitions and other programs and projects to undo colonialism and systemic racism. Furthermore, curatorial work lies within an institutional matrix. Inclusive curation can only go as far as the hosting organization. Ideally, it will work along with all of the departments of an organization to ensure that all visitors and stakeholders feel welcome and included. Diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion are paramount for curatorial work because they are lenses through which curators may inspect their work to ensure that it is representative of all relevant subjects, available to all who wish to experience it, and resonant for and respectful of all stakeholders.

Museums have, for centuries, supported and participated in power structures that have elevated the powerful and further limited the resources of marginalized people. This is why it is important for curators to work inclusively from the inception of a project through evaluation. Following a brief history, this essay will explore some practices and parameters that can inspire and inform inclusive curatorial work.

Historical Background

Since at least the mid-nineteenth century, people of color have used curatorial work for social justice in the United States. Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) offer an excellent institutional starting point for a history of anti-racist curatorial work. General Samuel Chapman Armstrong founded the museum at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) in 1868, making it the oldest museum at an African American institution. It continues in operation today, with a collection of 9,000 objects. Initially, the museum’s collections were not centered on African people, but rather began with Hawaiian and Polynesian objects, reflecting Armstrong’s history as a missionary in Hawai’i. The current mission is to

illustrate the cultures, heritages and histories of African, Native American, Oceanic and Asian peoples, as well as the works of contemporary African American, African and American Indian artists and three-dimensional objects which relate to the history and significance of Hampton University.[i]

The museum’s collection of African American fine art, the first in the nation, began in 1894.[ii] The museum provided an educational resource for the university and elevated its capacity and status, thereby also supporting the development of its Black students. The existence of the university and museum and the support of Black students were anti-racist moves on their own merit, providing Black communities with some insulation from the white supremacist culture in which they lived (and live today). By the 1890s, the exhibitions of the museum, like the broader university itself, were working for social justice simply by asserting and demonstrating that, for example, African Americans made fine art worthy of national and international attention.

A generation later, W.E.B. Du Bois’s curatorial effort of the American Negro Exhibit for the 1900 world’s fair in Paris—the Paris Exposition—became an example of an individual curator working in an anti-racist manner within a racist system. Shawn Michelle Smith tells the story of the exhibit in her fascinating book Photography on the Color Line.[iii] Although African Americans had been denied official participation in the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Thomas Junius Calloway invited Du Bois to create an exhibition of Black American life for the exposition. Du Bois contradicted white supremacists’ ideas and assertions with an exhibition of 363 photographs that, along with statistical charts, portrayed an elite African American patriarchy. His curatorial work was not without contemporary challenges. He marginalized African American women and constructed his own racial hierarchy of Black folks. But his statement was nevertheless crucially significant in its own time and context on the world’s stage.

In the United States in the 1960s, Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx Americans adapted and adopted social structures such as schools and museums to support communal autonomy and development.[iv] Many culturally specific institutions, such as the DuSable Museum of African American History (1961), the Anacostia Community Museum and the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience (1967), and el Museo del Barrio (1969), hail from this community museum movement.[v]

The movement saw museums as community centers and providers of necessary services. The National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) in Chicago used to be called the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum. That name is an artifact of its founding in the early 1980s, when it was struggling to communicate the intentional elision of museum and community center. But the museum’s legacy as a community center and museum informs the experience of visitors to this day: free admission and programming, warm and welcoming in winter, cool and refreshing in summer, and a blood drive around the Día de los Muertos exhibition all speak to this history.

Amy Lonetree’s essential book Decolonizing Museums (2012) nicely contextualizes the work of Native activists within and around this movement. As Native Americans worked for sovereignty, self-determination, and justice in many areas during the 1960s and ’70s, they also began to participate in planning and developing exhibitions about their cultures and advising museums that held their belongings on how to manage collections and, ultimately, the need to repatriate them. Likewise, Native Americans began to become museum professionals with an eye toward making change from within institutions and founding their own institutions. There were tribal museums before this period—Lonetree cites the Osage Tribal Museum (1938)—however, “the first significant wave of tribal museum development occurred in the 1960s and 1970s as part of a broader movement of economic development,” writes Lonetree.[vi] As of 2019, there were roughly 200 tribal museums in North America.

Community museums, culturally specific museums, and Native museums feature First Voice curation, stories told by, of, and for their own communities.[vii] Displaying these narratives was (and is) not only a matter of pride, education, and community maintenance; it was also a crucial step in moving histories of color into the mainstream. When Lonnie Bunch became the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), he was adamant that the African American story was an American story that concerned all Americans.[viii] Bunch’s work itself, from the Chicago History Museum to NMAAHC, grew out of the community museum movement.

In the thick of the debates on multiculturalism of the 1990s, the American Alliance of Museums (then the American Association of Museums; AAM) produced the landmark report Excellence and Equity (1992). Though education was an important part of the missions of many museums prior to this time, the report made it clear that working for equity—in this case through education—was a primary institutional mandate for accredited museums.[ix] It redefined excellence as requiring equity, stating that museums must “embrace cultural diversity in all facets of their programs, staff and audiences, in order to have any hope of sustaining vitality and relevance.”

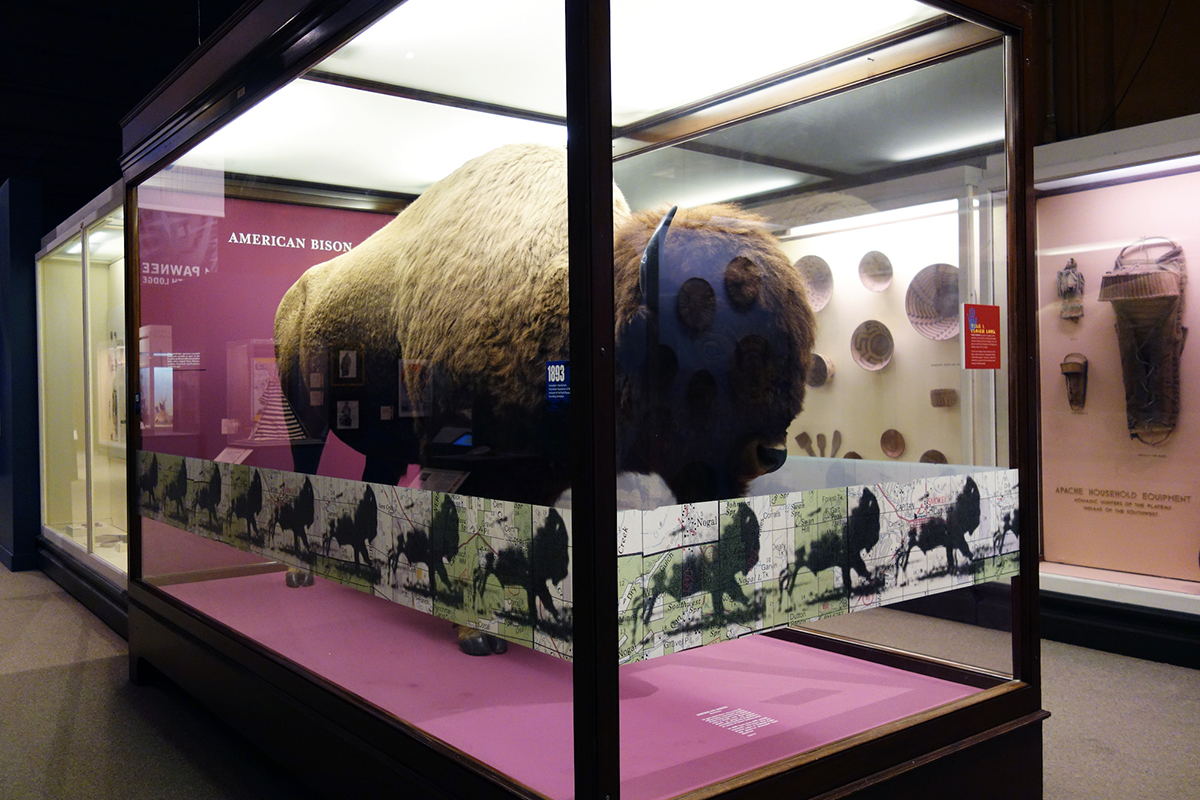

Across the world, museum professionals sought a diversity of voices in exhibitions. Michael Ames, director of the Museum of Anthropology (MOA) at University of Vancouver from 1974-1997 and 2002-2004, wrote prolifically about changing the role of the curator.[x] In Ames’s view, the curator was not the only individual with expertise. Rather, she could facilitate storytelling and elevate diverse stories inside and outside the museum. Ames sought to further engage visitors by making museum work more transparent. Under his direction, MOA pioneered the concept of visible storage, now known as the Multiversity Galleries. Though visible storage does not automatically lead toward inclusive practices, Ames meant it to unveil the agency behind curatorial work and include visitors in the exploration of collections that curators undertake.

Ames’s quest for transparency is still ramifying in the curatorial world through #MuseumsAreNotNeutral, the movement of La Tanya Autry and Mike Murawski, and other efforts to expose the agency behind curatorial work. A visitor confronted with the expansive Multiversity Galleries or another robust example of a collection in storage can begin to see that a curator must bring her own voice to bear on the subject matter in order to select the best objects for an exhibition. That is why, of course, the inclusive curator would do best not to act alone. Stakeholders—such as members of communities that are the subjects of exhibitions, neighbors of institutions, and other relevant groups—can help the curator to literally see the collections with new eyes and find the objects that speak to and include additional visitors.

In the early 1990s museums moved further toward more inclusive, and therefore more relevant, curatorial work. Fred Wilson curated Mining the Museum (1992-1993) for the Maryland Historical Society (MHS). (Like many museums working with artists and other contributors from outside, the MHS had to stretch from its comfort zone to eventually come to terms with Wilson’s work.) Wilson revealed how museums that truly wish to explore long histories of racism and systemic prejudice can use collections to do so. Indeed, artists can be powerful voices within museums that are not focused on the arts, shining a light on collections, as Wilson did, or exposing the challenges in an outdated and offensive exhibition, as Chris Pappan did at the Field Museum in Chicago. In these and many other cases, artists can challenge the museum’s institutional mindset and create friction. That friction can be productive in the long term by demonstrating that the museum can be relevant to groups it had previously not been serving. In short, artists can help museums with inclusive curation.

When we think of repatriation in the United States, we think of NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which Congress signed in 1990. However, this legislation was the result of decades of indigenous activism. Native Americans argued for repatriation in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s as they renewed their resistance to American colonialism. Meanwhile, First Nations and indigenous activists around the world, in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa, for example, lobbied for similar versions of state repatriations and other forms of respect for their sovereignty.

Though imperfect, NAGPRA changed curatorial work in the United States by codifying some of the preceding intention around inclusivity into law. NAGPRA offered one example of a group that could legally no longer be ignored: Native Americans. Legal protection for indigenous peoples is often not worth the paper it’s written on. Nevertheless, NAGPRA provided a mandate for museums to collaborate with indigenous people. In some instances, museums have taken this opportunity to repair the harm they have inflicted through practices of collecting, storage, and exhibition.

Diversity Equity Accessibility Inclusion (DEAI): The Framework for Inclusive Curation

With due respect to the acronym above, this essay addresses these terms in a meaningful order for inclusive curatorial work. Inclusion and equity go hand in hand. Here is a brief overview of these categories as I see them:

Equity: Curators and institutions must demonstrate a commitment to the equitable distribution of risks and rewards in society before marginalized communities can trust those institutions.

Inclusion: Provide a true and generous, respectful welcome to all different types of visitors and those who have yet to visit.

Diversity: Represent as broad a range of stakeholders as possible. Avoid thinking in terms of checking multicultural boxes.

Museums with boards, staff leadership, and front of house staffs dominated by people of privilege (white, wealthy, male, cisgender or some intersection of these categories) must make changes before people in marginalized communities can realistically believe that the institution will respect them. A multidimensional power dynamic exists along lines of race, class, gender, ability, immigration status, and more, and it does inflect relationships between museum professionals and their visiting publics. It places a rift between leaders, and by extension, their institutions and their stakeholders. Leaders must confront this power imbalance.

Though this must happen in every department of a museum, one important way to confront fraught relationships between institutions and stakeholders is to seek funders that support inclusive institutional goals. If efforts for equity or inclusion must fly under the radar, their power and creativity will be diminished. Fundraising is a lynchpin of this effort, since general operating support has become rare and project-based support has become the norm.

Accessible curatorial work is about all visitors being able to gain access to exhibitions and collections.

This may mean physical, emotional, or intellectual access, or some combination of all three. Whether accessibility means enabling touch in exhibitions, offering spaces to decompress, or using universal design, more often than not interventions that make exhibitions and collections more accessible to visitors with disabilities also make them more accessible to able-bodied visitors. One example of this is a social narrative that helps neurodivergent visitors manage expectations about their visit. This same narrative supports the visits of many others as well. Accessibility is another opportunity for museums to involve stakeholder communities in their curatorial work. A collaborator from a Deaf or Hard of Hearing community will be able to illuminate concerns about an exhibition that is taking shape or new ideas about planning a project in a different way, for example, than a partner who uses a wheelchair.

Practicing Inclusive Curation

Inclusion can manifest itself in many different ways, from low-income visitors who feel included because admission is free to queer visitors who feel included by a rainbow sticker on the front door, from English language learners who feel included by multilingual texts to visitors who are welcomed even when they have just stepped in out of the heat or cold or to use the restroom or a bench. True welcome is not conditional.

It is important for curators to consider who the stakeholders are for the stories they are telling. They could be local neighbors or culturally specific groups. In any case, involving stakeholders at the outset of a project is a sign of respect and can also provide excellent support in research and development. Once stakeholders are involved, they must be included in meaningful ways. Setting the agenda for a meeting, for example, is a kind of power; so, too, is selecting the subject matter and organization for an exhibition. The curatorial team can review its efforts to be inclusive at key intervals along the way.

Choosing the curatorial team should be purposeful. The goals of each project will help to determine whether it would benefit from a guest curator—perhaps an artist, an advisory group, community curation, visitor panels, a steering committee, or an in-house curator in conversation with others.

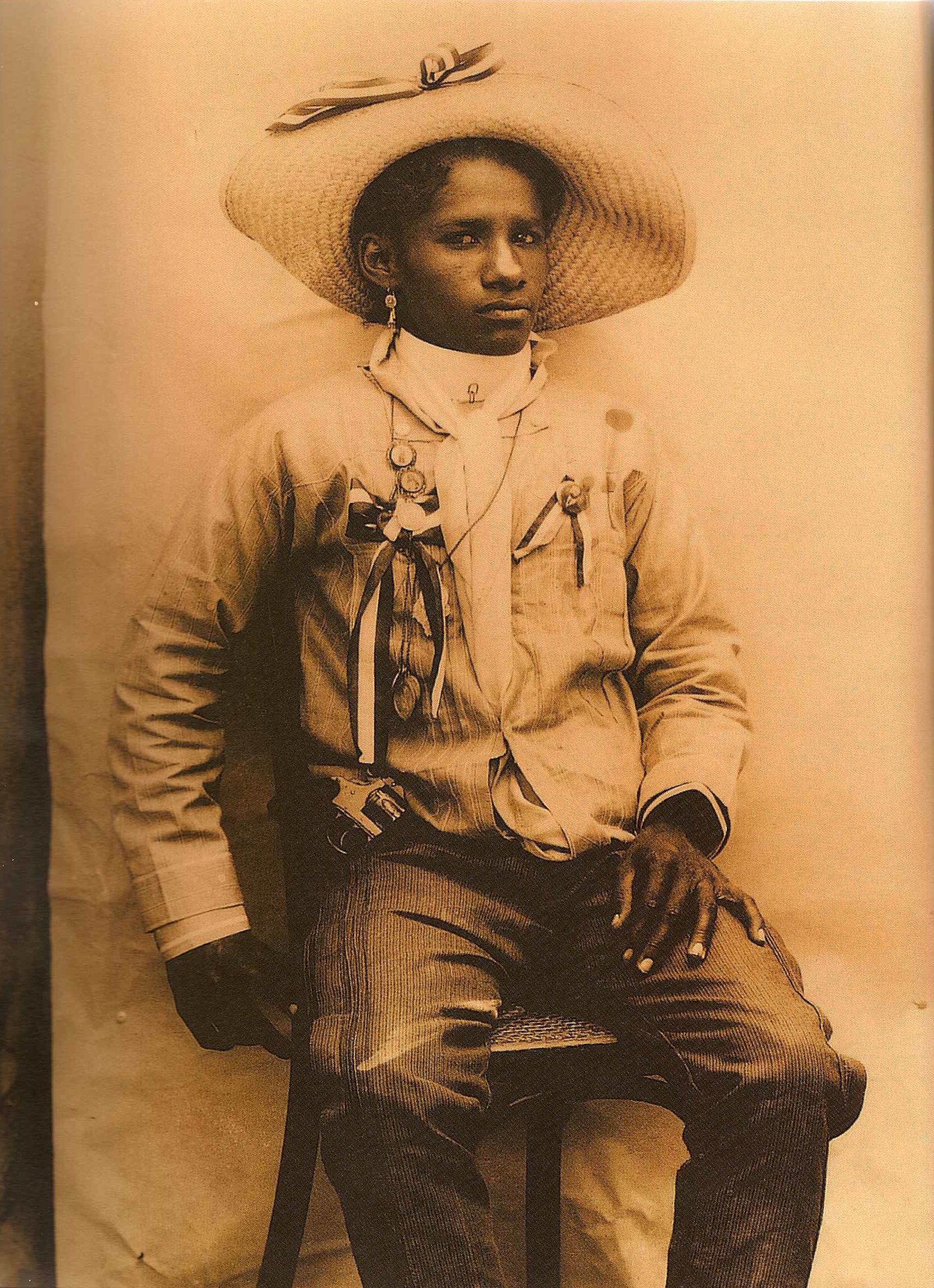

If a collecting institution is hosting the exhibition, mining the collections for unexpected material on the topic may be fruitful. During work on The African Presence in México at the NMMA, my colleagues and I found significant material that had always been used in other contexts, but spoke eloquently to our subject. For example, Portrait of a Female Soldier from Michoacán / Retrato de una soldadera de Michoacán by Agustín Casasola (see above), a photograph from 1910, shows a woman who is clearly of African descent. The famous, large-scale, imposing photograph became one of the signal images for the exhibition.

Once writing begins, ensure that the language is transparent about the agency of the curator and institution. Every exhibition expresses some subjectivity, and naming it will help curators to continue earning the trust of visitors and community members. As many scholars, organizers, and museum professionals have rightly pointed out, museums are not neutral. Portraying a false sense of objectivity can obscure support of the status quo. The trust museums build through transparency may encourage people to participate with the institution, thus making it more inclusive. A Declaration of Immigration is one example of an exhibition that did this at the NMMA. In 2007, the museum called for proposals from artists, asking them to “put a human face” on immigration and allow the audience to better understand the relationship between the United States and its Latin American neighbors. The resultant responses from artists shaped the tenor of the exhibition. In this instance, the unusually diverse group of artists (for this particular museum) were stakeholders.

Consider encouraging visitors to take action, especially when it will build empathy or include those who have been marginalized. In order to foster further inclusive curation, examine how visitors are using exhibits and collections and whether or not staff can adjust exhibitions during their run to make them more effective. Record who comes to an exhibition, and evaluate calls to action.

After an exhibition closes, maintain relationships with collaborators and plan for new projects. If one project is successful at including a community that previously did not visit, the work does not stop there. Check back with visitors, if possible. For example, at the end of the visit to Eastern State Penitentiary’s Prisons Today, visitors can answer a few short questions and the site will send them digital postcards at intervals after the visit, continuing the engagement into the future well beyond the visit. Involvement with partners and visitors may offer new insights into the collection or other institutional knowledge that can be carried forward. For example, after the exhibition Out in Chicago at the Chicago History Museum (CHM), which was inspired by the series of public programs “Out at CHM,” CHM began collecting on queer Chicago. The collecting initiative was one of the suggestions of queer partners in creating the exhibition. This demonstrates how creating an inclusive process for curating Out in Chicago, where there were queer curators and a queer visitor panel, can inspire exciting new directions that fit within the mission for the institution.

The global landscape of museums was an enormous resource of 80,000 museums before COVID-19.[xi] This body of institutions is diverse and consists of many museums emerging from Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) and other marginalized communities, as well as predominantly white institutions, or PWIs, in every discipline. Museums from BIPOC and queer communities have long histories developing practices that can inform PWIs as they develop or begin their work toward social justice. In many nations and fields of study, museum workers at PWIs are refusing the elitist, colonial histories of their institutions and creating change from within.[xii] Anti-racist and other inclusive work is becoming central to their institutions’ practices.[xiii] Curators from PWIs and BIPOC museums alike are mining their collections with fresh eyes, telling the histories of faces—and bodies—that might once have hidden in the shadows. Inclusive and especially anti-racist curatorial work is of particular urgency now. The history above demonstrates that inclusive museum work is largely about doing what we have long agreed needs to be done.

notes

[i] Hampton University Museum, “About Us,” http://wp.hamptonu.edu/msm/about-us/.

[ii] I usually avoid the term “fine art” because it draws an unnecessary and exclusionary distinction between the so-called fine arts and other art such as traditional, folk art, self-taught artists, and outsider artists. However, in this context it helps to highlight the way in which the Hampton University Museum sought to highlight the legitimacy of Black art.

[iii] Shawn Michelle Smith, Photography on the Color Line: W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 2004.

[iv] Steven Conn, Do Museums Still Need Objects? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009).

[v] For more on the community museum movement, see Fath Davis Ruffins, “Culture Wars Won and Lost: Ethnic Museums on the Mall, Part I: The National Holocaust Museum and the National Museum of the American Indian,” Radical History Review 68 (1997): 79-100, and “Culture Wars Won and Lost, Part II: The National African-American Museum Project,” Radical History Review 1998, no. 70 (1998): 78-101. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1998-70-78.

[vi] Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 17-19.

[vii] The history of the term, “first voice,” is difficult to trace. It originated around commemorations of the quincentennial of the encounter between Europeans and Indigenous people of the Americas. And there is an association between the term and terms such as “First Nations” and “First Peoples.” In “The First Voice in Heritage Conservation,” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 3 (2008), Amareswar Galla cites the workshops in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, during the International Year of Worlds Indigenous Peoples (1994). In 2018 Nina Simon, the museum guru and former director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, formed an organization called OF/BY/FOR All that directly builds on this history and attempts to spread it to mainstream organizations and predominantly white institutions (PWIs).

[viii] Though this is a subject he explored in his book, A Fool’s Errand, Bunch had been sharing this idea for many years prior to its publication.

[ix] Ellen Hirzy, Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums (Washington, DC: American Association of Museums, 1992).

[x] Michael Ames, Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992).

[xi] Richard Florida in Gail Dexter Lord and Ngaire Blankenberg, Cities, Museums and Soft Power (Washington, D.C: American Alliance of Museums, 2015), 2. Forbes estimated that a third of the roughly 35,000 museums in the US will close or merge because of the pandemic. For more on the state of museums in the pandemic, see the National Survey of COVID-19 Impact on US Museums.

[xii] See the free Toolkit by MASS Action (Museums as a Site for Social Action) as well as their initiative to keep museums accountable for statements of anti-racism or solidarity made in Spring 2020. Complete their survey here.

[xiii] This report card from Museums and Race can be useful in starting conversations about race in your institution.

Suggested Readings

Ames, Michael. Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992.

Bunch, Lonnie G., III. A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump. Illustrated edition. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2019.

Conn, Steven. Do Museums Still Need Objects? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Diamond, Anna. “Fifty Years Ago, the Idea of a Museum for the People Came of Age.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/fifty-years-ago-idea-museum-people-came-age-180973828/.

Galla, Amareswar. “The First Voice in Heritage Conservation.” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 3 (2008).

Hirzy, Ellen. Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums. Washington, DC: American Association of Museums, 1992.

Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Lord, Gail Dexter, and Ngaire Blankenberg. Cities, Museums and Soft Power. Washington, D.C: American Alliance of Museums, 2015.

Ruffins, Fath Davis. “Culture Wars Won and Lost: Ethnic Museums on the Mall, Part I: The National Holocaust Museum and the National Museum of the American Indian.” Radical History Review 68 (1997): 79-100.

_____. “Culture Wars Won and Lost, Part II: The National African-American Museum Project.” Radical History Review 70 (1998): 78-101. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1998-70-78.

Smith, Shawn Michelle. Photography on the Color Line: W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Author

~ Elena Gonzales is an independent scholar focusing on curatorial work for social justice and the author of Exhibitions for Social Justice (Routledge 2019) and co-editor of Museums and Civic Discourse: History, Current Practice, and Future Prospects (Greenhouse Studios, forthcoming). She received her doctorate in American Studies (2015) and her Master’s in Public Humanities (2010) from Brown University. She has curated exhibitions since 2006 and has taught curatorial studies since 2010. Contact: www.elenagonzales.org, [email protected], @curatoriologist.