“We need leadership!” is a cry heard from within the ranks of many organizations, but what does that mean, exactly? Often it is a longing for a clearer sense of direction or an explanation of an organization’s decision-making process. It may be the frustration caused by a lack of communication or employee inclusion in matters that affect them. It may even be a manifestation of outright contempt because of diminishing levels of trust and respect. Pleas for leadership are often as fundamental as the desire for a clear articulation of the core values of the organization—what it most values, as well as how it envisions its role and fulfills its mission. It may be about answering key questions: What kind of organization are we? What exactly are we doing? How, why, and for whom are we doing it?

It is the leader’s responsibility to guide these discussions, but first the nature and meaning of leadership must be fully understood. Like articulating what makes for good music and art, defining the nature of good leadership is challenging. It is largely a reflection of individual perspective and circumstances—what works for one leader may not work for another and what works in one situation may not work in another. There is no magic formula for effective leadership; it is far more art than science. The world is growing increasingly complex, and technology is changing the way we communicate and conduct business. The business environment (both for-profit and not-for-profit) is more competitive, and audiences are more sophisticated and demand more services. At the same time, political winds have shifted and financial resources are shrinking. The efficient use of time, money, people, and other resources is imperative. In her book Leading Museums Today, Martha Morris enumerates key leadership challenges that today’s museum leaders face, including issues related to environmental sustainability, security, repatriation, physical expansion (often with disastrous financial repercussions), and low wages. Lack of employee inclusion in decision-making is a serious concern, as is the need for new skills and flexibility in the workplace and meaningful recognition of diversity.[i]

What, Then, Is Leadership?

There are countless definitions of leadership, but they are often incomplete. While most definitions include similar elements—such as setting direction, aligning resources, and communicating with, motivating, and inspiring people—they often confuse leadership with management and do not recognize the true essence of leadership. Author and entrepreneur Kevin Kruse offers an excellent and concise definition, writing that leadership “is a process of social influence which maximizes the efforts of others toward the achievement of a goal.”[ii] It is social because it is largely about relationships with people and less about technical expertise or power. It is about influence because its primary goals are to align resources and communicate with and inspire people.[iii] It is about recognizing and maximizing the efforts of others because it acknowledges that people are our key resources. And, it is about achievement of a goal because there must be a clear and common mission with intended outcomes. Kruse’s definition might be enhanced by noting that effective leadership is not bestowed but instead earned and must be exercised in a way that motivates people to want to move in desirable directions.

Inclusion and Diversity

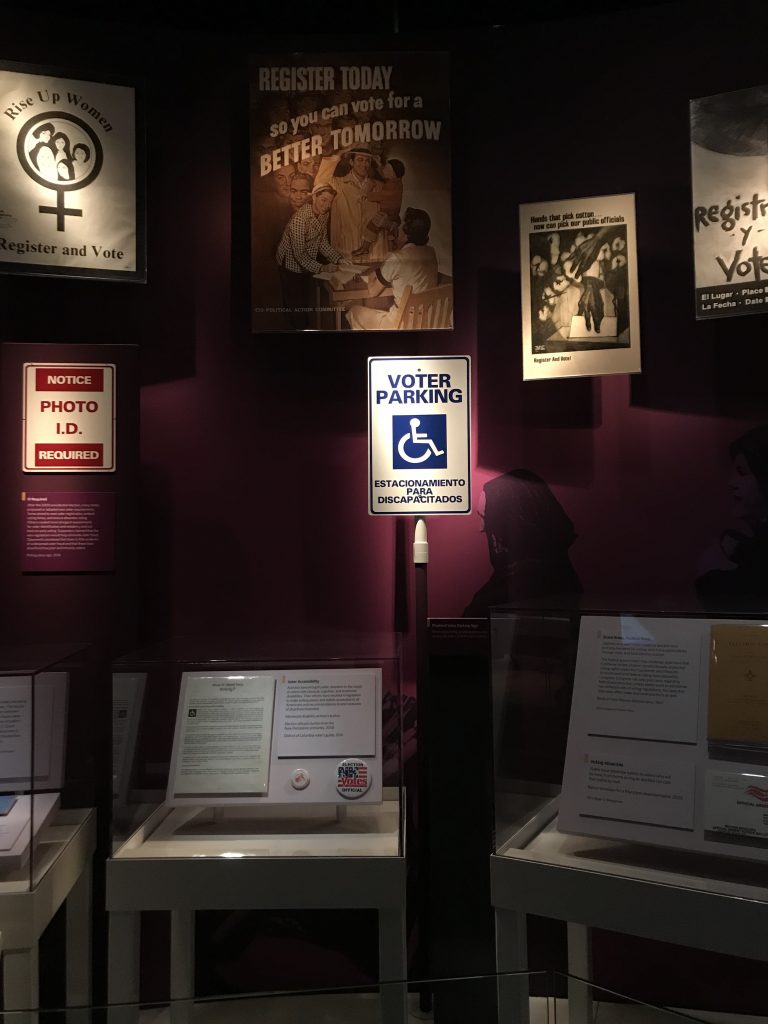

In 1965, only 5% of Americans were foreign born; by 2016, that number jumped to nearly 14% of the country’s population. Growing racial and ethnic diversity is changing the face of the United States. The Pew Research Center projects that by 2055 the U.S. will not have a single racial or ethnic majority.[iv] Yet, in a 2017 study of nonprofit boards, Boardsource noted that 90% of nonprofit CEOs and board chairs and 84% of all board members were white. Only 16% of board members were people of color. Two-thirds of CEOs expressed dissatisfaction with their organization’s level of leadership diversity.[v] According to a recent report by the American Alliance of Museums, 46% of museum boards are all white. While non-white people are 23% of the U.S. population, only 9% visit museums[vi] and 84% of jobs related to museum mission and leadership are held by white staff members.[vii] Furthermore, women continue to face significant gender discrimination, as Anne W. Ackerson and Joan Baldwin document in their recent survey of “Gender Equity in the Museum Workplace.” The survey, which also uncovered bias against LGBTQ individuals, recorded serious workplace discrimination in a range of forms, including salary inequity and verbal and sexual harassment. Clearly, we have work to do.

Leaders in our field must aggressively seek the diversity that reflects changing demographics lest we render ourselves irrelevant. This begins with individual and organizational commitment and leadership with a focus on both diversity and inclusion. Authors Patricia Bradshaw and Christopher Fredette note that organizations that promote diversity and inclusion have greater success when they employ both functional practices (policies, employment practices, recruitment, and training) and social practices (meaningful participation, relational connections, respect for different values, and trust). Functional practices alone do not create an inclusive organization because they often lead to patronizing attitudes and tokenism. Social practices are essential if organizations expect to be genuinely inclusive.[viii]

It is critical that we embrace a rich diversity of race, ethnicity, nationality, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, religion, socioeconomic status, and physical, intellectual, and developmental abilities in all we do. It broadens our audiences and encourages participation. It helps us develop more meaningful and relevant programs. It improves and more fully informs our collecting activity. It ensures our continued relevance and helps us make more meaningful contributions to the public we serve. It expands our fundraising efforts and makes us more sustainable. And, it makes our work and organizations better. Cultivating diversity and inclusion is the right approach and a smart philosophy to embrace, especially when it is guided by the phrase, “Nothing about us without us.”[ix]

Being Authentic and People-Centered

In order to create an environment that is truly diverse and inclusive we must genuinely live it in everything we do.

Good leaders in our field embrace the notion that we are, above all else, for and about people. Our organizations are managed by people, programs are presented by people, exhibits are developed by people—and they are for people. It is people, with their rich and diverse backgrounds, perspectives, and skills that help us foster a meaningful understanding of our world. Moreover, our work is not just for, and presented by, some people; it must be for, and presented by, all people.

Ultimately, diversity and inclusiveness are about relationships with people—welcoming people, being empathetic and listening to people, working with people—being decent to people, really. It is the leader’s role to set this tone and make it the very ethos of the organization. Being people-centered does not mean over-the-top hand-holding moments. It does not mean acquiescing to every need or demand. But, it does mean involving people in decision-making, listening to them, respecting their needs and perspectives, treating them with respect, and developing a keen sense of empathy. The essence of leadership is about creating relationships among people.

Effective leaders solicit involvement and listen to diverse groups outside the organization and develop leaders within the organization—nurturing their growth and maximizing their involvement. They insist on a diversity of perspectives and encourage dissent and they are not threatened when they hear criticisms. Effective leaders are willing to trust staff and delegate both responsibility and authority. They recognize that effective authority is shared authority.

Leaders lead by example and are sensitive to the needs of employees while balancing those with the needs of the organization and the public it ultimately serves. They communicate transparently and often. Leaders trust in order to be trusted and give respect in order to receive it. Authentic leaders build a repertoire of leadership skills as a result of their lifetime of experiences. Through experience, they learn how best to respond in certain circumstances. How a leader handles a major illness or an untimely death in the family, for example, provides a foundation of empathy and influences how that leader processes and manages difficult situations. It is these experiences that inform an inclusive leader.

Inclusiveness is essential to high performing organizations. Why not maximize all the people and resources we have available to us? Just as our institutional goal is to be inclusive to all people (our audiences), great leaders are inclusive within their organizations, encouraging participation at all levels, listening to concerns and ideas, delegating broadly, and embracing failures as an important part of innovation.

In a productive workplace, people participate in decision-making and feel valued for their contributions. They know how and why their efforts matter, leading to greater job satisfaction and productivity. They are motivated and strive to do their jobs at extraordinary levels with renewed enthusiasm. With proper support, encouragement, and recognition, people are capable of achieving amazing things—for themselves and the public they serve. This shared-authority democratic approach, rather than the top-down autocratic approach, allows for maximum participation and morale. But, one must also recognize that the responsible leader is still decisive and willing to make unpopular or difficult decisions when there is no clear agreement among stakeholders or there is a need to act quickly and decisively.

Great leaders are comfortable with the notion that being open-minded offers an opportunity for much learning. There is nothing to be gained from over-control. Leaders also foster a culture of calculated risk-taking and accept certain levels of failure as part of growth and experimentation. The best leaders are not afraid to expose their vulnerability and show that they, too, are human, imperfect, and make mistakes. Moreover, good leaders are viewed as thoughtful, calm, and deliberate—not petty and impulsive. True leaders are perceived as fair and honest and develop trusting and respectful relationships. They are the very embodiment of the values they espouse. They keep their eyes on a vision of what can be and do not let day-to-day distractions shake their convictions. Leaders have the courage to try new things, seek new audiences, and expand the reach of their organizations.

Inclusive leaders recognize the importance of being good to people. When they are, people are more committed, invested, happier, and productive, and they feel part of something that truly matters. These are the people who come to work not because they have to, but because they want to.

There is no recipe for how to become an authentic leader because, by definition, one cannot pretend to be authentic. But, why do we need to be authentic anyway? The simple answer is that, good relationships must be grounded in honesty, trust, and respect. Leaders know that for people to follow, people must believe in and trust the leader. They know the leader as a person and discern true levels of genuineness and honesty. Nothing is more hollow than a leader who stands for nothing in particular, is not trustworthy, betrays confidences, takes credit for the accomplishments of others, and quickly assigns blame to others for organizational failures. People know a con man. Leaders do what they say; they walk the walk. Good leaders know that it is actions that inspire beliefs—beliefs alone do not inspire sustained actions. Good leaders stand for something and act on it.

Becoming a Good Leader

There are thousands of works on leadership and lists almost as long of the personal characteristics necessary to become a good leader: honesty, integrity, vision, passion, enthusiasm, sense of humor, collegiality, trustworthiness, to name just a few. While they may all have some merit, the qualities of a good leader may be best summarized by author Daniel Goleman in his seminal work on emotional intelligence.[x] Goleman’s view is that as one moves up the leadership ladder it is not IQ and technical knowledge that become increasingly essential (although still important), but rather a well-developed sense of emotional intelligence. There is much evidence to suggest a strong link between organizational success and leaders’ emotional intelligence, especially in senior leadership roles.

Goleman defines emotional intelligence as understanding and managing our emotions and those of others. He identifies five major components to becoming a great leader through self-management of emotions and building relationships with others.

The first is Self-Awareness, which means that good leaders have a keen understanding of their strengths, weaknesses, emotions, and needs. They are honest with themselves and others and know how their feelings affect them and others. Self-aware leaders know their strongly held values and principles and live by them. They know where they are going and why. They understand their strengths and have confidence in them. They also understand their weaknesses and do not set themselves up for failure. They are risk takers, but not reckless. They know their limits and those of the organization. They assess themselves honestly and do the same for their organizations.

Self-Regulation is the ability to manage and control emotions, and to think before acting. A self-regulated leader does not pound on the table or throw pencils. The leader is in control (not out of control), reasonable, and chooses their words and actions carefully. The leader is respected because of fairness and well-considered statements and actions. The leader’s approach is calm, not frenzied, and tends to encourage the same behavior from subordinates. Judgment is suspended and impulses are controlled. Reflection, thoughtfulness, and comfort with change are hallmarks. Although sometimes misconstrued as lacking passion, the self-regulated leader knows that high emotion and impulsiveness are often counterproductive.

Motivation is another key component of a great leader. Leaders are driven and strive to exceed their own and others’ expectations. They are motivated by a desire to achieve. Passion for the work is real and they take great pride in their achievements and those of the organization. They are always raising the performance bar and optimistic about the organization achieving more. They see opportunities, not problems. They are deeply committed to the organization and want it to be the best of its kind. Their attitude and enthusiasm are contagious.

Empathy may seem akin to mushiness and non-businesslike behavior, but what it really means is treating people through an understanding of their emotional needs and reactions. This is especially important in a fast-paced environment in which changes happen frequently. It is important to understand and appreciate everyone’s viewpoint to gauge the full implication of decisions and their impact. Related to this is the importance of coaching and mentoring, understanding the needs and aspirations of employees, and responding to them. This often leads to a happier workforce and more retention. Understanding employees as people and practicing cross-cultural sensitivity are hallmarks.

Social Skill is the last component of emotional intelligence. Leaders with this skill set are very good at working with people and establishing rapport and relationships. They are experts at managing teams and have keen abilities of persuasion. They recognize that leaders cannot achieve things alone, and if the leader cannot communicate and build relationships and teams, little will be accomplished. They are skilled at finding common ground and excel at articulating and leading change.

Ultimately, leadership is about getting work done through people and understanding that individual and organizational success are inseparable. Recognizing and cultivating this important truth is perhaps the most important leadership lesson of all.

Notes

[i] Martha Morris, Leading Museums Today (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 2-7.

[ii] Kevin Kruse, “What is Leadership?” Forbes, www.forbes.com, April 9, 2013.

[iii] John P. Kotter, John P. Kotter on What Leaders Really Do (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Books, 1999), 51-62.

[iv] D’vera Cohn and Andrea Caumont, “10 demographic trends shaping the U.S. and the world

in 2016,” Pew Research Center, March 31, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/03/31/10-demographic-trends-that-are-shaping-the-u-s-and-the-world/.

[v] Leading with Intent: 2017 National Index of Nonprofit Board Practices (Boardsource, 2017), 10-11.

[vi] “Facing Change: Insights from the American Alliance of Museums’ Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion Group,” American Alliance of Museums, p. 9, https://www.aam-us.org/programs/diversity-equity-accessibility-and-inclusion/facing-change/.

[vii] Brian Boucher, “Mellon Foundation Study Reveals Uncomfortable Lack of Diversity in American Museums,” Artnet, August 4, 2015.

[viii] Patricia Bradshaw and Christopher Fredette, “The Inclusive Nonprofit Boardroom: Leveraging the Transformative Potential of Diversity,” Nonprofit Quarterly, December 29, 2012, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/the-inclusive-nonprofit-boardroomleveraging-the-transformative-potential-of-diversity/.

[ix] The phrase “nothing about us, without us” is closely associated with the disability rights movement.

[x] Daniel Goleman, “What Makes a Leader?” Harvard Business Review Best of HBR 1998, 1-11.

Suggested Readings

Ackerson, Anne W., and Joan H. Baldwin, Leadership Matters: Leading Museums in an Age of Discord. Revised edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield/AASLH, 2019. See also, the companion website.

Baldwin, Joan H., and Anne W. Ackerson, Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Workplace. New York and London: Routledge, 2017.

DePree, Max. Leadership is an Art. Dell Publishing, 1989.

Drucker, Peter. Managing the Nonprofit Organization: Principles & Practices. New York: Harper Collins, 2005.

Harvard Business Review. On Leadership. Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, 2011.

Kotter, John P. John P. Kotter on What Leaders Really Do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Books, 1999.

Maxwell, John C. Developing the Leader Within You. Thomas Nelson Inc, 1993.

Morris, Martha. Leading Museums Today. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018.

Peters, Thomas J., and Robert H. Waterman, Jr. In Search of Excellence. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

Roberts, Wess. Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun. New York: Warner Books, 1987.

Author

~ Brian Alexander is Visiting Professor of Museum Administration and Director of the Institute for Cultural Entrepreneurship at the Cooperstown Graduate Program, SUNY Oneonta, in New York. Prior to coming to Cooperstown, Alexander worked for 38 years in the museum field. Among other positions, he served as President & CEO of the National World War I Museum, President & CEO of the Historic Annapolis Foundation, Executive-Vice President & Director of the Shelburne Museum, and Director of the State Museum of North Dakota. He has also been a trustee of the American Association for State & Local History. He can be reached at [email protected].